-

Ex-post probability assessments from expected goals statistics

The expected goals statistics (xg) in football/soccer games have been around since 2012, but I have only really started to notice them properly in the last few years. They are an interesting attempt to quantify and objectify randomness in football games. In this blog post, I want to explain how one could use these statistics to compute probabilities of the various results of a game after the game was played.

Computing probabilities of how a game could have ended after it was played does perhaps seem a bit silly. After the game, we already know how it ended. However, it could be quite relevant to a sober judgment about a team’s performance. Sometimes journalists heap praise on a team and its manager after a game that ended with a tight 1:0, where the opposition had plenty of chances that they did not take; sometimes journalists condemn a team and its manager for a game lost with a wonder strike in the last minute. I often feel that there is generally a lack of a proper appreciation of the randomness in football games.

Of course, you could ask whether there is any randomness in football at all. One can take the view that everything is deterministic and just a question of (Newtonian I think would suffice) physics. But I would think that most people would agree that there are some factors that nobody can control and nobody can completely foresee (even if they understand physics). An unexpected sudden gust of wind might make the difference between a long-range shot hitting the bar so that the ball goes in, or hitting it so that the ball stays out. An invisibly slightly wetter patch of grass might make the difference between a sliding tackle getting to you in time to take the ball off you, or just falling a tad short of that.

Once you allow for some such randomness, the next question would be how one should quantify such randomness. In fact, can we quantify it in terms of probabilities and even if we can, would we all come to the same conclusion? There are some instances of randomness that researchers (on the whole) would refer to as objective uncertainty, also often called risk. A good working definition of objective uncertainty (or risk) would be that it is such that most people assign the same probabilities to the various events (events = things that can happen). Think of the uncertainty in a casino in games such as Poker, Roulette, Blackjack, Baccara, or Craps. Most people would agree that the chances of the ball in roulette coming up, say, 13, is 1/37, because there are 37 numbers (0 to 36), symmetrically arranged around the roulette wheel. If someone told me that they feel lucky and think that the probability that their number, say 13, will come up is 50%, I would even believe that they are just wrong.

Outside the casino, it seems that most of the uncertainty we encounter is not objective in this sense. Uncertainty is often in the eye of the beholder, as people like to say. This is even true in the casino at times. If you have two aces in your hand playing poker, your assessment of you winning this round will be different from that of your opponents, who don’t know which cards you are holding. Similarly, someone who has observed the weather over the last 48 hours would probably make different weather predictions for the next day than someone who has not done so.

There is a deep philosophical debate in the literature (google the common prior assumption) as to whether we should model different individuals’ different probability assessments over some events as deriving exclusively from them having seen different information, or whether individuals could also sometimes be modeled as just having different beliefs about something – period. Luckily, this debate is not hugely relevant to what I want to discuss here. But I do believe that it is just empirically correct to say that different people would often quantify randomness differently (for whatever reason). You might suspect that some people don’t quantify uncertainty into probability at all. Probably true, but one has to be careful. People might not be able to tell you what probability they attach to certain things, but they might behave as if they do. I also don’t want to get into this either, though.

What I wanted to say is that I believe that football games have uncertainty that is not typically considered objective. Ask two different people (perhaps ideally people who bet on such things) about the chance of how a game would end and you will probably get two different answers. But I do like attempts to objectify the randomness in football games. And the xg approach is a pretty good attempt. As far as I understand, see again this post, an xg value for any chance at goal in the game is computed using a form of (probably logit- or probit-like) regression given a large data set of past shots, where shot success is explained with variables such as distance from goal, the angle of the shot, and many other factors. Personal characteristics do not seem to be used. This means that the same chance falling to Kylian Mbappe or a lesser-known player would have the same xg. We might come back to that later. [Actually, now that I am finished with this post, I see that we won’t. A shame.]

I want to get to one example that I will work through a bit, to eventually come up with what I promised at the beginning, an after-the-game assessment of the probabilities of how the game could have ended. Let me take the, for Austrians, slightly traumatic experience of the recent round of 16 game between Austria and Turkey at the 2024 European championship in Germany, which Austria lost 1:2. I found two good sources that provide an xg-value for this game: the Opta Analyst and a website called xgscore.io. Both provide xg-values for the two teams for the entire game: this is the sum of all xg-values for each goalscoring chance. The Opta Analyst makes it an xg of 3.14 for Austria and an xg of 0.92 for Turkey (when you click on the XG MAP in the graphic there) and in the text they make it: “Austria can consider themselves unfortunate, having 21 shots to Turkey’s six and recording 2.74 expected goals to their opponent’s 1.06.” Xgscore.io finds an xg of 2.84 for Austria and an xg of 0.97 for Turkey. So even they do not all agree.

An objective assessment of expected goals for each team is not quite enough yet to compute the probabilities of how the game could have ended. I need an assessment of not only the expected goals but also their variance. In fact, two teams with the same xg of 1, could have a very different distribution of goals scored. One team could have had an xg of 1 because they had one chance and that one chance had an xg of 1; perhaps it was a striker getting the ball one meter in front of goal with the goalkeeper stranded somewhere else on the pitch. Then this team would have scored 1 and only 1 goal, and that with certainty. Another team with the same xg of 1 could have had two chances that both had a 50% of going in. This team could have scored 0, 1, or 2 goals, with 0 and 2 goals 25% likely and 1 goal 50% likely.

I don’t think that Opta (or any other source) regularly provides the xg details for each goal-scoring chance that I would need to compute these distributions. But for the game Austria versus Turkey, I can get a sense of these distributions from the XG MAP provided on the analyst.

Let me simplify and take an xg of 3 for Austria and 1 for Turkey. I will now calculate the probability distribution of the various outcomes of this game under two different scenarios. In both scenarios, I assume that Turkey had two (stochastically independent) chances, both with a 50% likelihood of success, a 0.5 xg. The two sum up to one. This makes the number of goals scored by Turkey, call it X, a binomial distribution with n=2 tries and a success probability p=0.5. In reality, Turkey had 5 or 6 chances, with all but two of them rather speculative efforts – see the XG MAP. In the first scenario, I assume Austria’s xg of 3 is decomposed into six (stochastically independent) chances with an xg of 0.5 each. This is not quite correct, but also not a terrible approximation of reality. This means the number of goals Austria scores, call it Y, is also binomial with n=6 and p=0.5. All I need to do now is to compute the probabilities that X>Y (Turkey wins), X=Y we have a draw, and X<Y (Austria wins). I asked chatgpt to do so; it does it correctly and provides not only the results but also the various steps of calculation. In this first scenario, I got a roughly 3.5% probability of Turkey winning, an 11% probability of a draw, and an 85.5% probability of Austria winning.

In the second scenario, I keep Turkey the same, but I now assume that Austria’s goals scored Y is binomial with n=10 and p=0.3. That means Austria had 10 chances with xg values of 0.3 each. Again, not quite correct, but also not a terrible approximation of reality. With chatgpt’s help, I now get a roughly 11% probability of Turkey winning, a 12.6% probability of a draw, and a 76.4% probability of Austria winning.

It is interesting to see how much of a difference there is in the two scenarios. If I had the full data for this game I could compute the probabilities more accurately, which would be a bit harder because each goal-scoring chance will typically have a different xg value and the total number of goals scored by each team is not simply binomial. But with some computing effort, the various probabilities could still be calculated. I would like it if Opta (or any other source) were to provide these after-the-game winning probabilities induced by their xg statistics.

These after-the-game probabilities could now be compared with the before-the-game probabilities implied by the betting odds. I found betting odds for Austria vs Turkey here. In my notation, these are 2.05 for Austria winning, and 3.4 each for a draw and for Turkey winning. These translate into probabilities of 45.33% that Austria wins, 27.33% for a draw, and 27.33% that Turkey wins (I am making some assumptions here, ignoring the commonly observed favorite-longshot bias).

This does not mean that the betting odds were wrong, of course. It only means that, in some sense, Austria positively surprised the “market” in the game by producing a probably higher-than-expected xg-value, while in another sense, they negatively surprised the market by not winning.

So, assume that the xg-scores are indeed a good way to objectify the randomness of what happens in a game. Having detailed xg information, for every goal attempt, would allow us to compute objective probabilities for all possible ways the game could have ended. While I would very much like to see these after-the-match probabilities reported, and to see them used for a sober judgment of a team’s effort in a game, I also know that there is something we ignore when we do so. All this is under the assumption that the game would have been played equally irrespective of whether some of the earlier attempts at goal were successful or not. This is, of course, unrealistic. I, for instance, had the feeling that England tended to play better and with more urgency, creating more chances, when they were behind in a game than when they were in front or drawing. A team’s game plan is, generally, likely conditional on how the game unfolds. The randomness entailed in these game plans, however, is much harder to quantify.

-

The Euro 2024 betting market

During the recent European football championship, I recorded betting odds of winning the competition for all teams. I tried, and mostly succeeded, in recording these odds after every game from a website called oddschecker.com who say that they always report the best (that is highest) available betting odds across all sports betting providers. Email me if you’d like me to send you this data. One can think of sports betting markets as toy financial markets. In this blog post, I explore this toy market through my self-collected data set and see what insights we can glean from it (assuming glean means what I think it means).

I like to record these betting odds (not quite as on oddschecker.com) for an event (for instance that England wins the competition) as a number o that is the Euro amount you will receive for every Euro you place on this bet if the event turns out to be true (for instance that England wins the competition) – otherwise you lose your Euro. Betting odds are essentially determined by supply and demand, just like stock prices, as I explain in more detail in this previous blog post. I thought I would here, however, translate these odds into something more akin to a stock value. For every team, we can consider an asset that would pay out € 1000, say, in the event that this team wins the whole tournament. The value of such an asset at any point in time is given by 1000/o, because this is how much money you would have to place on this team to receive € 1000 if that team wins eventually. By the way, 1/o can also be seen as the break-even probability, of the event that this team wins the tournament, that would make you as a bettor/investor indifferent between betting on this team or not. If your subjective probability assessment of this event exceeds 1/o you should bet on this team, if not you should not (see the Appendix for why you “should”).

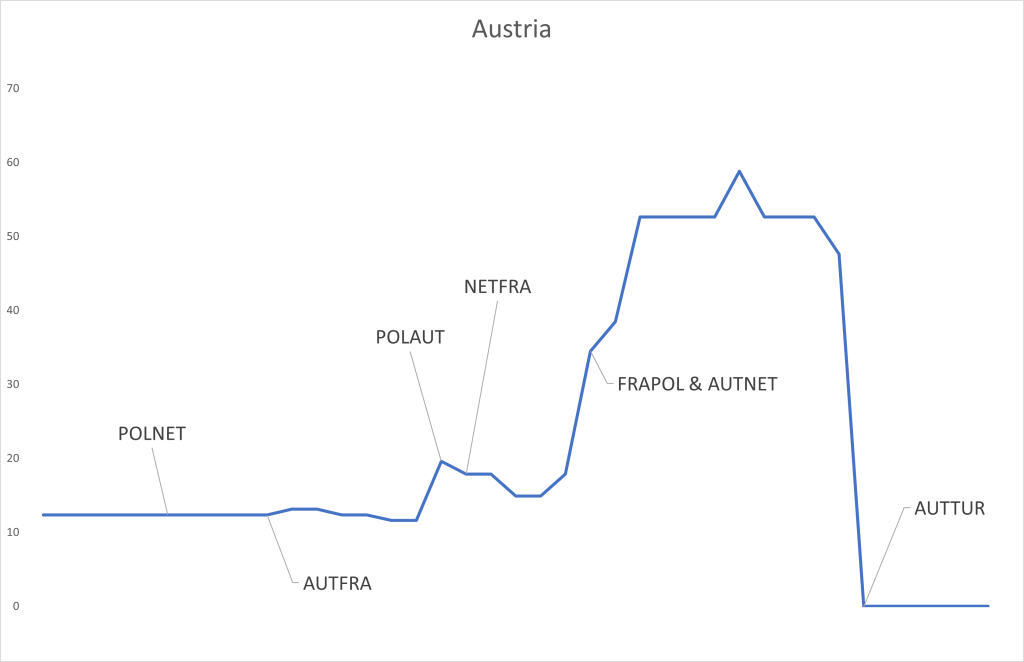

The above graph shows the value of this asset for Austria winning the competition. I have marked when certain games, most relevant for Austria, occurred. This asset “Austria” started before the tournament began with a value of around € 12,3 (because the betting odds were 81). This means, recall, that the “market” gave Austria a 1,23% probability of winning the competition at this time. When Austria lost to France 0:1 something remarkable happened: the value of “Austria” did not change. This means that the market expected some such result and performance from Austria, the result did not surprise one way or the other. It did not make the market think of Austria’s chances having improved, nor that their chances were diminished. My reading is that while a loss should have diminished the market’s assessment of Austria’s chances to win the competition, the otherwise solid performance in that game counterbalanced this. When Austria beat Poland 3:1 the value of the asset “Austria” went up to about € 19,6, the market now gave Austria a higher chance of winning the competition after this win. There are smaller changes in the value of this asset along the way, based on certain results and performances in other games, but when Austria then beat the Netherlands 3:2 and France drew with Poland 1:1, making Austria top of their group, the asset “Austria” went up to (after some little while – oddschecker may not have been quick enough with their updates) € 52,6 (giving Austria a 5,26% chance of winning the tournament). The next and last big change happened when Austria lost to Turkey in the round of 16 and the asset’s value went to zero.

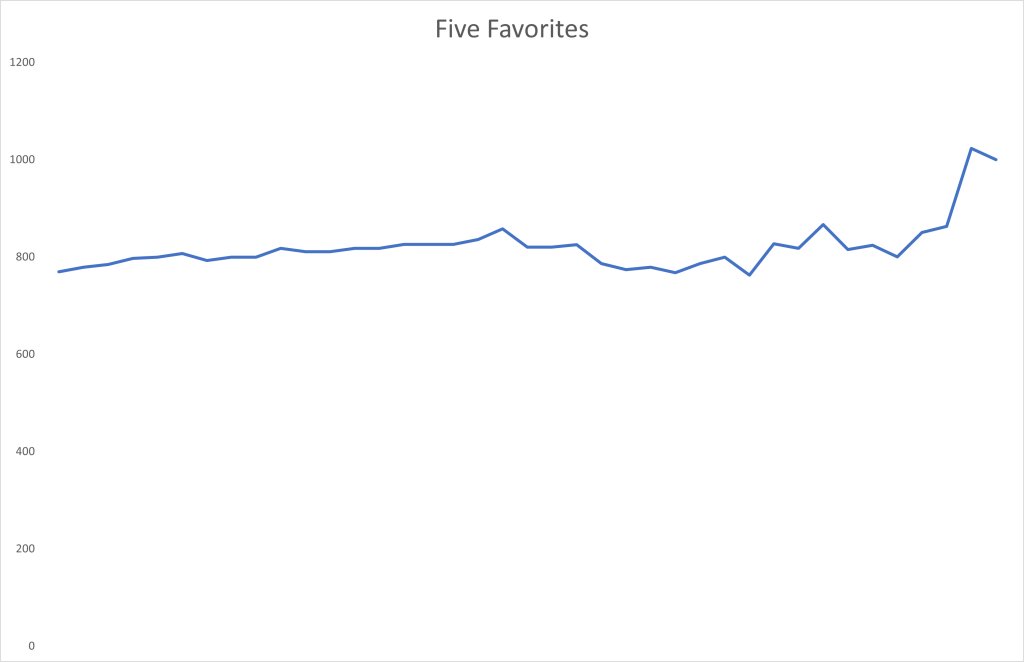

I find it interesting to look at the total value of the five favorites to win the tournament to begin with: England (odds of 5), France (5,25), Germany (6,5), Portugal (8), and Spain (10). The total value of these five assets (as shown in the graph above) started at € 769,3 (the market giving it a 76,93% chance of one of these teams winning the competition). This value changed remarkably little throughout the tournament, rising to a peak of € 866,7 after France beat Belgium in the round of 16, until before the final when there were only favorites left. [Btw, note that all five of these favorites went to at least the quarterfinals, and if one of them lost a game then only against another favorite.]

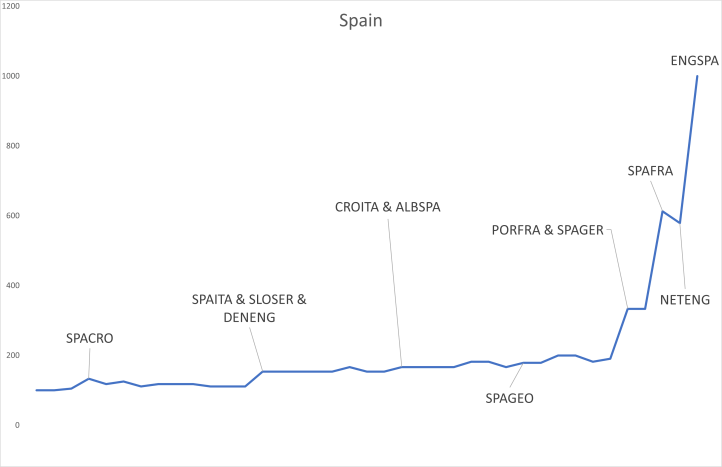

Let us, finally, look at Spain, the eventual winner of this tournament. In the graph above, I marked mostly those games that Spain was involved in. Spain seems to have gradually and consistently surprised a bit, or at least their market-perceived chances of winning the competition and, thus, the value of the asset “Spain” steadily increased over time. It started at a value of € 100 and reached a value of € 613 after Spain beat France in the semi-final, then briefly went down to a value of € 579 after England beat the Netherlands to reach the final – I guess this means that England was deemed by the market the more difficult opponent – before Spain finally won the tournament and the asset “Spain” paid out € 1000.

Appendix

When I said earlier that “[i]f your subjective probability assessment of this event exceeds 1/o you should bet on this team” I do mean that you should. Let me clarify. First, I think your carefully considered subjective probability assessment of any event should essentially never exceed its odds-induced break-even probability of 1/o, so you should never bet (see my point further below). But if it did happen that your (carefully considered) subjective probability exceeded 1/o then you should bet on this event. This is so because you “should” be risk-neutral. This in turn is so because the randomness in one such bet on a sports game is most likely idiosyncratic, I mean statistically independent from anything else that goes on in the world. It is, especially, most likely stochastically independent of the financial market. In the language of finance, any such asset based on sports bets has a CAPM beta of zero, where an asset’s beta is a measure of its correlation with the world financial market portfolio. Moreover, there are millions of such bets available, all independent from the financial market and most likely all more or less independent of each other. This means that if you put a small amount of money on any bet with a positive (carefully considered) subjective expected value, you would (in your carefully considered assessment) make a positive amount of money essentially without risk, because of the law of large numbers. Ok, this is assuming that you find many such bets, which maybe you shouldn’t be able to.

My subjective probability of any event I could bet on is essentially always lower than its break-even probability 1/o. This is for two reasons. First, I to a large extent believe in the efficient market hypothesis (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Efficient-market_hypothesis), this is the hypothesis that all relevant information that anybody in the world (outside of insiders who are prevented from trading) could have about the value of a financial asset is reflected in the price of that asset. In the context of sports bets, all this information is hypothesized to be reflected in the betting odds. My belief in the efficient market hypothesis, especially for sports bets, is empirically somewhat justified for instance through some tests I made in a previous blog post. Second, you may ask how my probability assessment can be lower than the break-even probability induced by betting odds for all possible bets. Surely probabilities add up to one, and if one of my probability assessments is lower than its break-even probability then another will be larger. You are right that my subjective probability assessments sum up to one, but the odds-induced break-even probabilities do not! This is because the betting company keeps a small percentage share (around 5% or so) and all odds are a bit too small, so the break-even probabilities sum up to more than one. So, I never bet. While I would, therefore, advise most people not to bet (at least not in a big way), I am sort of glad that some do, because I do like to study the betting market!

-

Homo oeconomicus sitting in the corner

A real estate development group has bought the land next to the house of someone I know and they are now planning to build an apartment complex. To do so they need planning permission and one step in that process involves the developers meeting with the neighbors, and anyone else that may be concerned, to present the building project. This is moderated by a magistrate of some kind, who also takes note of all possible concerns that the neighbors and others may have. I was asked to come along. In this blog post, I want to share some aspects of my experiences at this meeting that speaks to two things: one, the homo oeconomicus assumption, some version of which is often made in economic models, and two, corner solutions of constrained maximization problems.

When I started to study economics, coming from math, I was a bit surprised by some of the assumptions that are made in economic models. It was easy to see that many, well actually all of them, were just empirically wrong. In my studies, I didn’t have classes on the philosophy of science or the art of producing new knowledge and insights. So, it took me a long time to appreciate what economic models are good for. They are not meant to be anywhere near a completely empirically accurate account of the real world. Rather they are highly simplified toy models that make a point, identify a theoretical force or relationship, or clarify the validity of an argument, all of which help us understand certain real-life problems better, even if they do not provide a perfect fit to any real-world data that you might be looking at.

In particular, I had huge misgivings about the often-recurring homo oeconomicus assumption of economic agents as fully informed razor-sharp mathematical optimizers with clear objectives, expressed as very precise utility functions. To me, everyday economic agents seemed far away from such an ideal. I felt that I, for instance, often didn’t know what I wanted, wasn’t fully informed of my options and their consequences, and was often unsure, even when I knew what I wanted if I ended up choosing the best path forward. Of course, there is now a lot of useful economic literature on weakening all these assumptions, and I am still very sympathetic to this literature. But I have also learned to appreciate the extreme homo oeconomicus assumption in the following simpler form: many people in many situations have pretty clear goals, which they pursue, be it consciously or unconsciously, given whatever limited options they have at their disposal.

For instance, and now we finally get to the meat of this post, let me look at these property developers. They showed us their, admittedly rather beautiful, architectural plans of the new proposed housing complex. They explained it to us. They then took questions from the concerned neighbors, who (I inferred) would have preferred nothing to be built next to them. Let me zoom in on an interesting bit of dialogue between some of the neighbors and the architect. I don’t recall the numbers perfectly anymore, so please forgive me if they are wrong. Also, they all spoke German, and I will provide a fairly liberal translation only. A first neighbor (FN): “So, basically, there will be a huge wall just at the end of my property that will overshadow my whole garden?” The architect (A): “No, of course not. We deliberately planned that the house will be some distance away from the boundary between the two properties.” FN: “Ah, how far away will it be?” A: “At least 2 meters.” FN: “Aren’t there some government rules that specify a minimum distance between houses and their neighbor’s properties?” A: “Yes, there are. The minimum distance is 2.10 meters.” FN: “And how far away is your planned house?” A: “Hm, let me see. Ah, here it says. It looks like it is 2.10 meters.” A second neighbor (SN): “But you are planning three floors, isn’t that too high?” TA: “No, three floors are allowed.” SN: “But that makes that wall facing my garden about three times two and a half meters tall, about seven and a half meters altogether. Is that really allowed?” A: “No, that is not allowed, but the wall that you will see will only have two floors and is just 5 meters tall and that is allowed.” SN: “But aren’t there three floors on your plan here?” A: “Yes. But the third floor is placed back a bit, so it is not so visible from your garden.” SN: “Is that allowed?” A: “Yes, if you place the floor back sufficiently, 75 centimeters back in fact.” SN: “Ah, and how far back are you planning the third floor?” A: “Hm, let me see. If you look here, you will see that it is, what is it, ah 75 centimeters. Perfectly ok.”

There was plenty more along these lines. I guess, it is not too bad an assumption, at least in this present case, that the property developers knew what they wanted (as much floor space and as many units as possible), subject to planning permission constraints, and they optimized. And, in the present case that delivers corner solutions of the underlying mathematical problem that they seem to be solving.

-

The helmet and safety jacket dilemma

When my children bike to school, they wear a helmet. When they use a (non-electric) scooter, they don’t. They also don’t wear any bright and highly visible safety jackets when using either. Why not? I certainly would prefer if they did and I tell them so. But they don’t want to. They have a variety of arguments, the jacket doesn’t fit properly, they can’t see well with the helmet, et cetera. But I suspect that the real reason is that it is not considered cool to wear a helmet on a scooter or a safety jacket on either scooter or bike. I speak of children, but I have the feeling that adults are not so different. Nobody used to use seatbelts (although why that may have been considered cool, I don’t know) and nobody wore a helmet on motorbikes and now, when everybody has to, nobody seems to mind. Not many adults wear helmets when they are biking and, at least in Graz where I live, not many use helmets even on those e-bikes, some of which look like and are almost as fast as motorbikes. In this post, I want to provide a simple game theoretic model that allows me to study how wanting to be cool could influence people’s decisions when it comes to helmets and such things and to see how much of a social dilemma this might induce.

I will model this problem as a population game. There is a continuum (a large number) of (each on their own non-influential) people. Each person decides to wear a helmet or not (when biking or scooting or whatever it is). When making this decision they care about the proportion of others that wear a helmet. I will allow people to have somewhat different preferences from each other, not everybody feels the same way about wearing helmets. The model can be summarized by two ingredients, a personal characteristic

that is distributed in the population according to some cumulative distribution function

, and a utility function

, a person’s utility when wearing a helmet, that depends on the proportion

of people that wear helmets and on their characteristic

. Finally, I will assume that not wearing a helmet gives any person a utility of zero.

For simplicity, I will choose a specific, slightly crude, functional form for this utility function:

where the

is the (obviously assumed positive) net benefit from wearing a helmet (increased chance of survival minus any discomfort that wearing a helmet might induce) and

is the feeling of shame when wearing a helmet for all to see. This latter expression is chosen to have a few key features. First, the higher

the lower the feeling of societal shame for wearing a helmet. This is supposed to capture the idea that the more people wear helmets the less one has to worry about being cool by not wearing one. We can discuss this, probably not always justified, assumption a bit more later. Second, the higher

the higher the feeling of societal shame for wearing a helmet. Thus, higher types, that is, people with a higher

, have a higher lack-of-coolness-cost of wearing a helmet. By assumption, a person will wear a helmet if the utility of doing so exceeds that of not doing so, that is when

(I am breaking indifference in favor of wearing helmets, but this is not important). By design, this means that a person will wear a helmet if and only if

. In other words,

is the proportion of people wearing a helmet in the population that a person of type

requires, for them to wear a helmet themselves. Note that a person with a

will always wear a helmet, regardless of how many others wear helmets, and that a person with a

will never wear a helmet.

In this world that I just created, there is a best and worst possible outcome. The fewer people wear helmets the (weakly) worse off everyone is: either they don’t wear a helmet anyway, then they are unaffected, or they wear a helmet when many people do, but not when only a few do, in which case their utility has gone down, or they wear a helmet in either case, then their feeling of shame for wearing one has gone up. The best outcome is the one, in which everyone (other than a type

) wears a helmet, in which case nobody would have any lack-of-coolness costs and everyone would get a utility of

The worst outcome is the one, in which nobody (other than types

) wears a helmet, in which case they all get a payoff of zero (or

, for types

).

We are now looking for (Nash) equilibria of this game. An equilibrium proportion

of people wearing a helmet must be such that when

is the proportion of people wearing a helmet, exactly a proportion

people will want to do so. The proportion of people who would want to wear a helmet, given

is given by the cumulative distribution function

In equilibrium, we, thus, simply must have that

Suppose we assume, as seems reasonable, that there are people who will always wear a helmet regardless of how many others wear a helmet, and that there are people who will never voluntarily wear a helmet. This means that

and

Given that

must be a weakly increasing function, we then have that there must be at least one

between zero and one, for which

So, we must have at least one equilibrium. What equilibrium we can get all depends on

the distribution of

that is, the distribution of people’s attitude towards the societal shame they feel when wearing a helmet.

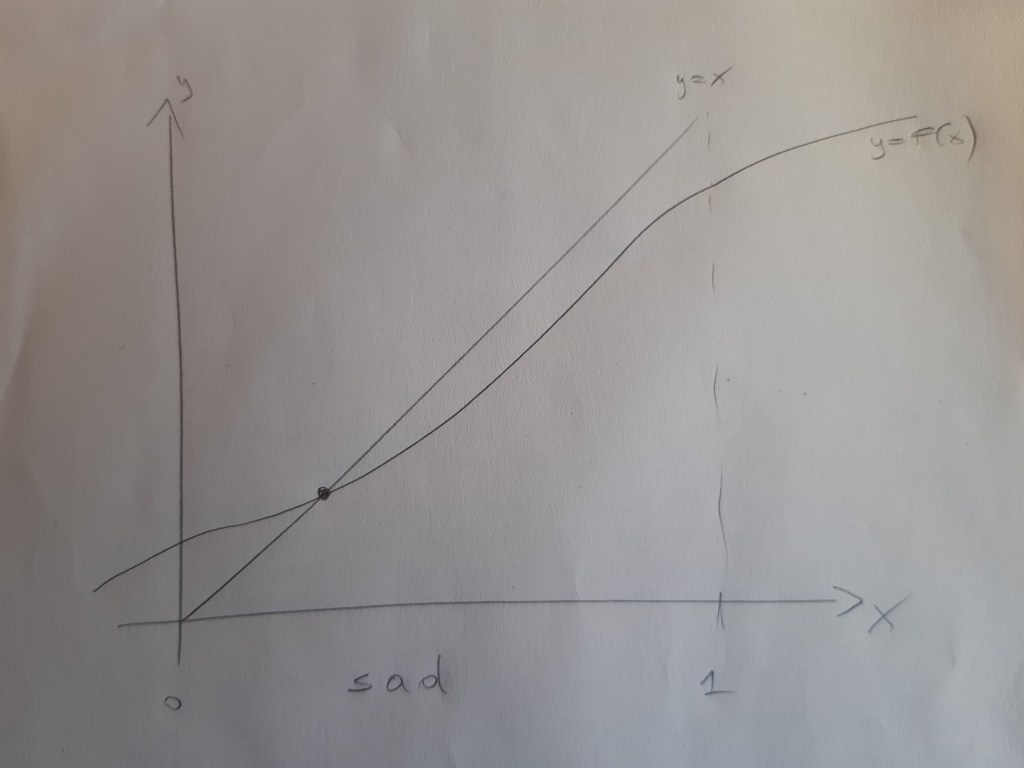

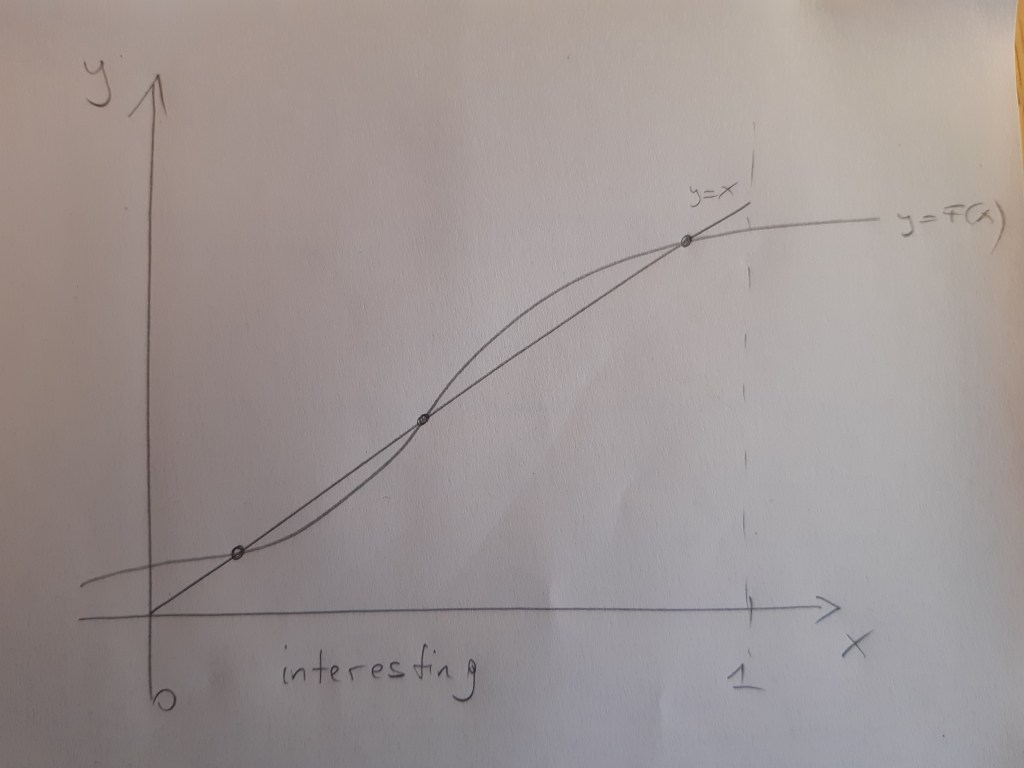

To discuss some of the many different possible situations I use a series of high-tech pictures with the proportion of people wearing a helmet

on the x-axis. They all depict two lines, the identity

and the cumulative distribution function

.

In the situation that I denoted “lucky,” there are many people with a low

which means most people don’t suffer too much societal shame when wearing a helmet. This can be seen in that the function

rises quickly and stays above the identity function

for most values of

In this case, there is a unique equilibrium and it has a high proportion of people wearing helmets. By the way, if you are wondering how we would get to this equilibrium, there is a dynamic or evolutionary justification. Suppose nobody is wearing a helmet and helmets have just been introduced. Then

is the proportion of people who immediately take up helmets. Call this

Others now realize that there are a proportion of

people wearing helmets. This induces others to take up helmets. It would induce about

new people to take up helmets. We then have a proportion of

of people wearing helmets. This goes on and on, until we hit the equilibrium point where

And when we get there, this would be all great.

In contrast, in the picture that I titled “sad”, most people are very worried about societal shame. This can be seen in the slow rise of

in

and it then staying below the identity function. In this situation, there is again a unique equilibrium, in which, however, the proportion of people wearing a helmet is low. This is sad, because, as I have noted above, the societal optimum would be that everyone wears a helmet.

How could we get from the latter situation to the former? There are, actually, many ways a government could try to make that happen. One option would be to make helmets mandatory (and to enforce this rule at least to some extent) so that, presumably, people suffer a cost for not wearing a helmet, the fine they might receive when caught, which makes wearing a helmet relatively more attractive for them. This could be expensive, as you need to hire and pay police personnel to enforce the rules. Another option that the government could try to use is to fund an advertising campaign aimed at making people less worried about not being cool. They could try to make wearing helmets cool, instead, for instance. This could have just the same effect. Under both policy measures, if done well, the function

would shift to the right, which probability theorists call a first-order stochastic dominance shift. This would have the effect of shifting the equilibrium proportion of helmet wearers up.

There is a third possible situation, that I depict in the figure entitled “interesting,” in which there are multiple equilibria. The low and high helmet-wearing equilibria are both dynamically stable (a dynamic process as the one I described above would lead to these points when the system starts in the vicinity of these points). The middle equilibrium is not dynamically stable. The lower equilibrium is initially more likely, as it makes sense to think that at some initial point, nobody wore helmets. If this is the situation that we are facing, then introducing a law to make helmets mandatory needs to be implemented and enforced only for a short time, until the proportion of helmet wearers exceeds the middle (unstable) equilibrium. After that we end up in the good equilibrium without any need for further enforcement.

This post has become a bit longer than I intended. Of course, one could debate whether or not there really is a social dilemma here (meaning my utility functions are possibly wrong). Perhaps, people just value the freedom of having the wind blow through their hair when scooting much more than the added chance of survival from a possible accident. Then a helmet law would make everybody just worse off. An advertising campaign might not be so bad in that case. There are many other things one could question, but I won’t do this now.

-

Rational Herding on the Autobahn

The speed limit on the Autobahn south of Graz to the Austrian/Slovenian border varies. Sometimes the speed limit is 130 km/h and sometimes it is 100 km/h. The speed limit is also not constant for the whole stretch of Autobahn and, after some distance from Graz, it definitely becomes 130 km/h. I don’t fully understand how these speed limit decisions are made and I also don’t quite know at which point the speed limit is definitely 130 km/h. I believe it has something to do with local pollution, so it may depend on weather or traffic conditions, but I don’t quite know. So, at least for me, the speed limit is a random variable and this is probably also true for most people. Now, what should I do when I am somewhere on this Autobahn at a point, where I am not sure what the speed limit is? I rationally “herd”.

Let me explain. To inform people about the speed limit, there are some, not many, electronic signs that can be programmed from some central place. The other day, when I drove south from Graz, I was initially in no doubt about the speed limit. One of these electronic signs just outside Graz was clearly showing 100 km/h. So, I attached a probability pretty close to 1 to the event (as probability theorists like to call it) that the speed limit is 100 km/h and I drove accordingly. A little bit later there was another one of these signs and that sign, if anything, just made my subjective probability assessment of the event that the speed limit is 100 km/h even closer to 1, and I still drove accordingly. I then drove on for quite some time, perhaps 10 or 20 kilometers, a little bit lost in thought, when I realized that I hadn’t seen a speed limit sign recently. Did I miss them? There should have been one, I thought, and I probably didn’t notice it. So, what was the speed limit now?

I also noticed, and that possibly prompted my reevaluation of my speed limit beliefs, that I was being overtaken by some cars that were going pretty fast. You need to know that drivers on the Austrian Autobahn, by and large, obey the speed limits. Of course, this is not 100% true, and one has to take this into consideration. But with any car that I estimated to be going about 130km/h when they overtook me, my subjective probability assessment that the speed limit is 100km/h went down and down and down. After about 4 or 5 cars went past me at about 130 km/h, I was at the point where I attached a sufficiently high probability to the event that the speed limit is 130km/h that I also went 130 km/h. I didn’t need this probability to be 1, as the chances of being caught speeding and being fined for it are not that high, and I, of course, preferred to get to wherever I wanted to get to earlier rather than later.

After a few minutes of driving speedily along, I encountered the next speed sign and it showed 100 km/h. There is a small probability that the speed limit had been temporarily (I mean on that stretch of Autobahn that I just had been on) 130 km/h, but it is a small one. So, I and the other drivers were wrong. Or were we? I would like to say that I was not wrong because I did not attach a probability of 1 to the event that the speed limit was 130 km/h. And possibly the other drivers also did not. The question is this: did or did we not also take into account that some of the other drivers that were going 130 km/h were going 130 km/h because they had seen others go 130 km/h and had formed their belief on a similar basis as I did. It is quite possible (and perhaps we did take this into account) that the first driver that we all saw going 130 km/h did this by mistake or just because they didn’t care. Perhaps this one driver was already enough, however, for a second driver to change their beliefs sufficiently for them to increase their speed and that, in turn, prompted a third and that a fourth and that me to start to go faster.

All of these decisions could be declared as being rational decisions as long as none of us were fooled into believing with certainty that the speed limit was now 130 km/h. We imitated the behavior of others before us, rationally thinking that their behavior provided evidence that the speed limit was 130 km/h. Often this assessment would have been correct. In the present case, it was not. This is, unfortunately, something that can happen when people rationally “herd on” others’ behavior. You may want to think about this when, for instance, you see an advert stating that one million people have bought whatever-it-is they are advertising and, therefore, the advert claims, so should you. But why have those others bought whatever-it-is? Maybe for the same reasons as you are just about to buy it? Because others have bought it? There is possibly less information in this statement than you think. For those who are interested: The literature on rational herding goes back to at least the 1992 paper “A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades” by Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, and Welch and is still going strong, see the 2021 NBER working paper “Information Cascades and Social Learning” by the same authors plus Omer Tamuz.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.