During the recent European football championship, I recorded betting odds of winning the competition for all teams. I tried, and mostly succeeded, in recording these odds after every game from a website called oddschecker.com who say that they always report the best (that is highest) available betting odds across all sports betting providers. Email me if you’d like me to send you this data. One can think of sports betting markets as toy financial markets. In this blog post, I explore this toy market through my self-collected data set and see what insights we can glean from it (assuming glean means what I think it means).

I like to record these betting odds (not quite as on oddschecker.com) for an event (for instance that England wins the competition) as a number o that is the Euro amount you will receive for every Euro you place on this bet if the event turns out to be true (for instance that England wins the competition) – otherwise you lose your Euro. Betting odds are essentially determined by supply and demand, just like stock prices, as I explain in more detail in this previous blog post. I thought I would here, however, translate these odds into something more akin to a stock value. For every team, we can consider an asset that would pay out € 1000, say, in the event that this team wins the whole tournament. The value of such an asset at any point in time is given by 1000/o, because this is how much money you would have to place on this team to receive € 1000 if that team wins eventually. By the way, 1/o can also be seen as the break-even probability, of the event that this team wins the tournament, that would make you as a bettor/investor indifferent between betting on this team or not. If your subjective probability assessment of this event exceeds 1/o you should bet on this team, if not you should not (see the Appendix for why you “should”).

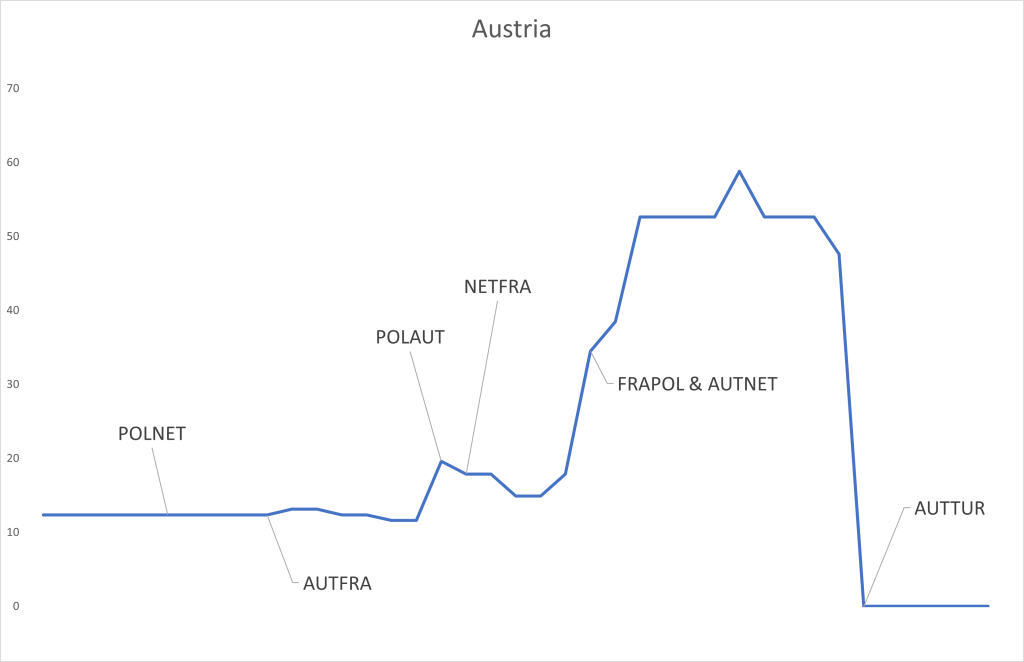

The above graph shows the value of this asset for Austria winning the competition. I have marked when certain games, most relevant for Austria, occurred. This asset “Austria” started before the tournament began with a value of around € 12,3 (because the betting odds were 81). This means, recall, that the “market” gave Austria a 1,23% probability of winning the competition at this time. When Austria lost to France 0:1 something remarkable happened: the value of “Austria” did not change. This means that the market expected some such result and performance from Austria, the result did not surprise one way or the other. It did not make the market think of Austria’s chances having improved, nor that their chances were diminished. My reading is that while a loss should have diminished the market’s assessment of Austria’s chances to win the competition, the otherwise solid performance in that game counterbalanced this. When Austria beat Poland 3:1 the value of the asset “Austria” went up to about € 19,6, the market now gave Austria a higher chance of winning the competition after this win. There are smaller changes in the value of this asset along the way, based on certain results and performances in other games, but when Austria then beat the Netherlands 3:2 and France drew with Poland 1:1, making Austria top of their group, the asset “Austria” went up to (after some little while – oddschecker may not have been quick enough with their updates) € 52,6 (giving Austria a 5,26% chance of winning the tournament). The next and last big change happened when Austria lost to Turkey in the round of 16 and the asset’s value went to zero.

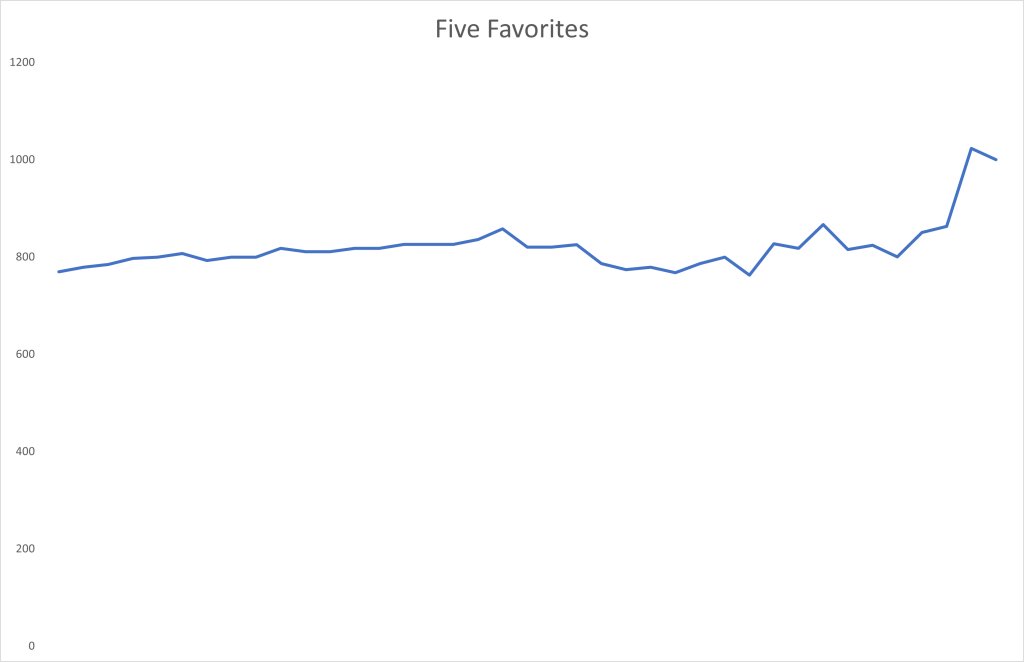

I find it interesting to look at the total value of the five favorites to win the tournament to begin with: England (odds of 5), France (5,25), Germany (6,5), Portugal (8), and Spain (10). The total value of these five assets (as shown in the graph above) started at € 769,3 (the market giving it a 76,93% chance of one of these teams winning the competition). This value changed remarkably little throughout the tournament, rising to a peak of € 866,7 after France beat Belgium in the round of 16, until before the final when there were only favorites left. [Btw, note that all five of these favorites went to at least the quarterfinals, and if one of them lost a game then only against another favorite.]

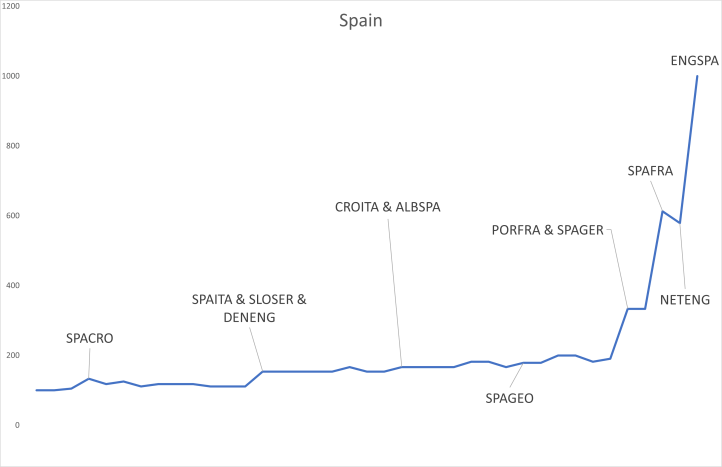

Let us, finally, look at Spain, the eventual winner of this tournament. In the graph above, I marked mostly those games that Spain was involved in. Spain seems to have gradually and consistently surprised a bit, or at least their market-perceived chances of winning the competition and, thus, the value of the asset “Spain” steadily increased over time. It started at a value of € 100 and reached a value of € 613 after Spain beat France in the semi-final, then briefly went down to a value of € 579 after England beat the Netherlands to reach the final – I guess this means that England was deemed by the market the more difficult opponent – before Spain finally won the tournament and the asset “Spain” paid out € 1000.

Appendix

When I said earlier that “[i]f your subjective probability assessment of this event exceeds 1/o you should bet on this team” I do mean that you should. Let me clarify. First, I think your carefully considered subjective probability assessment of any event should essentially never exceed its odds-induced break-even probability of 1/o, so you should never bet (see my point further below). But if it did happen that your (carefully considered) subjective probability exceeded 1/o then you should bet on this event. This is so because you “should” be risk-neutral. This in turn is so because the randomness in one such bet on a sports game is most likely idiosyncratic, I mean statistically independent from anything else that goes on in the world. It is, especially, most likely stochastically independent of the financial market. In the language of finance, any such asset based on sports bets has a CAPM beta of zero, where an asset’s beta is a measure of its correlation with the world financial market portfolio. Moreover, there are millions of such bets available, all independent from the financial market and most likely all more or less independent of each other. This means that if you put a small amount of money on any bet with a positive (carefully considered) subjective expected value, you would (in your carefully considered assessment) make a positive amount of money essentially without risk, because of the law of large numbers. Ok, this is assuming that you find many such bets, which maybe you shouldn’t be able to.

My subjective probability of any event I could bet on is essentially always lower than its break-even probability 1/o. This is for two reasons. First, I to a large extent believe in the efficient market hypothesis (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Efficient-market_hypothesis), this is the hypothesis that all relevant information that anybody in the world (outside of insiders who are prevented from trading) could have about the value of a financial asset is reflected in the price of that asset. In the context of sports bets, all this information is hypothesized to be reflected in the betting odds. My belief in the efficient market hypothesis, especially for sports bets, is empirically somewhat justified for instance through some tests I made in a previous blog post. Second, you may ask how my probability assessment can be lower than the break-even probability induced by betting odds for all possible bets. Surely probabilities add up to one, and if one of my probability assessments is lower than its break-even probability then another will be larger. You are right that my subjective probability assessments sum up to one, but the odds-induced break-even probabilities do not! This is because the betting company keeps a small percentage share (around 5% or so) and all odds are a bit too small, so the break-even probabilities sum up to more than one. So, I never bet. While I would, therefore, advise most people not to bet (at least not in a big way), I am sort of glad that some do, because I do like to study the betting market!

Hi Christoph,

I love reading your blogs. This one was very interesting.

I’d like to see the data you gathered if you can share it.

Thank you, Ram

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Ram, thank you! I sent you the data file by email.

Christoph

LikeLike

[…] probabilities implied by the betting odds. I found betting odds for Austria vs Turkey here. In my notation, these are 2.05 for Austria winning, and 3.4 each for a draw and for Turkey winning. These […]

LikeLike