When my children bike to school, they wear a helmet. When they use a (non-electric) scooter, they don’t. They also don’t wear any bright and highly visible safety jackets when using either. Why not? I certainly would prefer if they did and I tell them so. But they don’t want to. They have a variety of arguments, the jacket doesn’t fit properly, they can’t see well with the helmet, et cetera. But I suspect that the real reason is that it is not considered cool to wear a helmet on a scooter or a safety jacket on either scooter or bike. I speak of children, but I have the feeling that adults are not so different. Nobody used to use seatbelts (although why that may have been considered cool, I don’t know) and nobody wore a helmet on motorbikes and now, when everybody has to, nobody seems to mind. Not many adults wear helmets when they are biking and, at least in Graz where I live, not many use helmets even on those e-bikes, some of which look like and are almost as fast as motorbikes. In this post, I want to provide a simple game theoretic model that allows me to study how wanting to be cool could influence people’s decisions when it comes to helmets and such things and to see how much of a social dilemma this might induce.

I will model this problem as a population game. There is a continuum (a large number) of (each on their own non-influential) people. Each person decides to wear a helmet or not (when biking or scooting or whatever it is). When making this decision they care about the proportion of others that wear a helmet. I will allow people to have somewhat different preferences from each other, not everybody feels the same way about wearing helmets. The model can be summarized by two ingredients, a personal characteristic that is distributed in the population according to some cumulative distribution function

, and a utility function

, a person’s utility when wearing a helmet, that depends on the proportion

of people that wear helmets and on their characteristic

. Finally, I will assume that not wearing a helmet gives any person a utility of zero.

For simplicity, I will choose a specific, slightly crude, functional form for this utility function: where the

is the (obviously assumed positive) net benefit from wearing a helmet (increased chance of survival minus any discomfort that wearing a helmet might induce) and

is the feeling of shame when wearing a helmet for all to see. This latter expression is chosen to have a few key features. First, the higher

the lower the feeling of societal shame for wearing a helmet. This is supposed to capture the idea that the more people wear helmets the less one has to worry about being cool by not wearing one. We can discuss this, probably not always justified, assumption a bit more later. Second, the higher

the higher the feeling of societal shame for wearing a helmet. Thus, higher types, that is, people with a higher

, have a higher lack-of-coolness-cost of wearing a helmet. By assumption, a person will wear a helmet if the utility of doing so exceeds that of not doing so, that is when

(I am breaking indifference in favor of wearing helmets, but this is not important). By design, this means that a person will wear a helmet if and only if

. In other words,

is the proportion of people wearing a helmet in the population that a person of type

requires, for them to wear a helmet themselves. Note that a person with a

will always wear a helmet, regardless of how many others wear helmets, and that a person with a

will never wear a helmet.

In this world that I just created, there is a best and worst possible outcome. The fewer people wear helmets the (weakly) worse off everyone is: either they don’t wear a helmet anyway, then they are unaffected, or they wear a helmet when many people do, but not when only a few do, in which case their utility has gone down, or they wear a helmet in either case, then their feeling of shame for wearing one has gone up. The best outcome is the one, in which everyone (other than a type ) wears a helmet, in which case nobody would have any lack-of-coolness costs and everyone would get a utility of

The worst outcome is the one, in which nobody (other than types

) wears a helmet, in which case they all get a payoff of zero (or

, for types

).

We are now looking for (Nash) equilibria of this game. An equilibrium proportion of people wearing a helmet must be such that when

is the proportion of people wearing a helmet, exactly a proportion

people will want to do so. The proportion of people who would want to wear a helmet, given

is given by the cumulative distribution function

In equilibrium, we, thus, simply must have that

Suppose we assume, as seems reasonable, that there are people who will always wear a helmet regardless of how many others wear a helmet, and that there are people who will never voluntarily wear a helmet. This means that and

Given that

must be a weakly increasing function, we then have that there must be at least one

between zero and one, for which

So, we must have at least one equilibrium. What equilibrium we can get all depends on

the distribution of

that is, the distribution of people’s attitude towards the societal shame they feel when wearing a helmet.

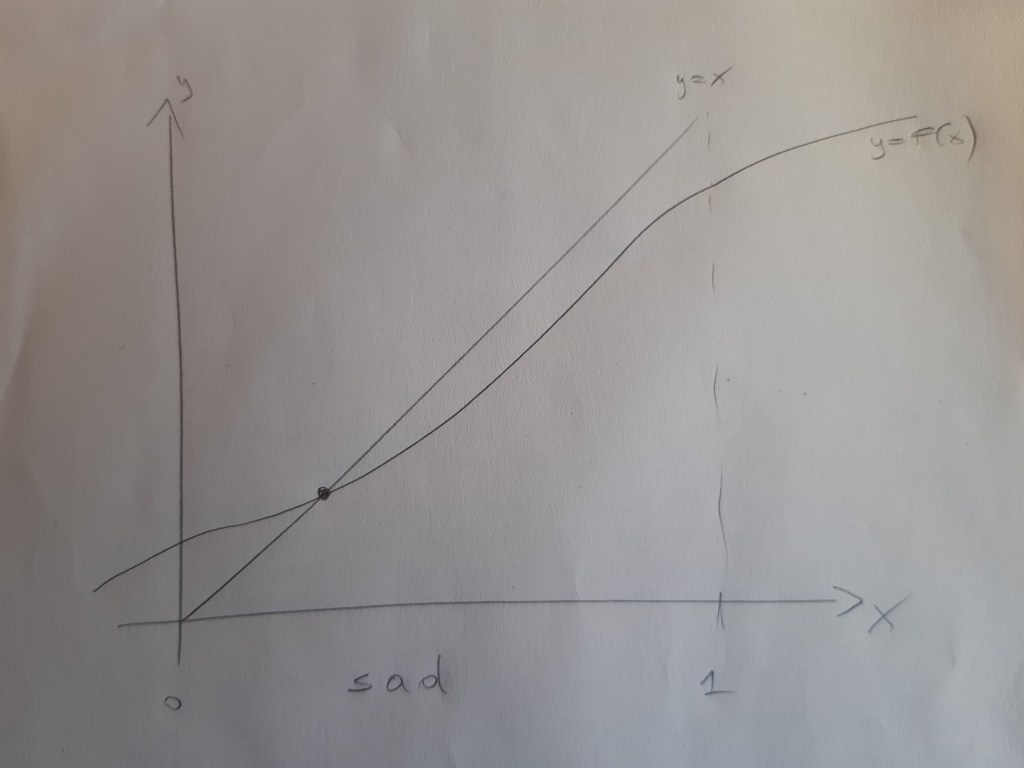

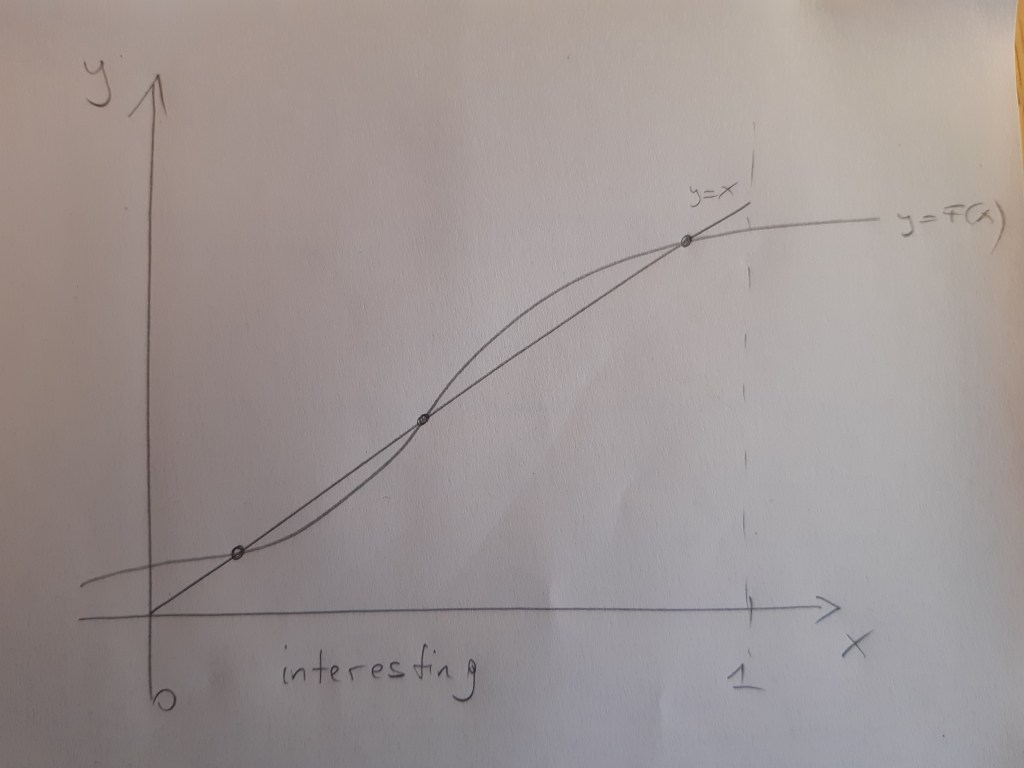

To discuss some of the many different possible situations I use a series of high-tech pictures with the proportion of people wearing a helmet on the x-axis. They all depict two lines, the identity

and the cumulative distribution function

.

In the situation that I denoted “lucky,” there are many people with a low which means most people don’t suffer too much societal shame when wearing a helmet. This can be seen in that the function

rises quickly and stays above the identity function

for most values of

In this case, there is a unique equilibrium and it has a high proportion of people wearing helmets. By the way, if you are wondering how we would get to this equilibrium, there is a dynamic or evolutionary justification. Suppose nobody is wearing a helmet and helmets have just been introduced. Then

is the proportion of people who immediately take up helmets. Call this

Others now realize that there are a proportion of

people wearing helmets. This induces others to take up helmets. It would induce about

new people to take up helmets. We then have a proportion of

of people wearing helmets. This goes on and on, until we hit the equilibrium point where

And when we get there, this would be all great.

In contrast, in the picture that I titled “sad”, most people are very worried about societal shame. This can be seen in the slow rise of in

and it then staying below the identity function. In this situation, there is again a unique equilibrium, in which, however, the proportion of people wearing a helmet is low. This is sad, because, as I have noted above, the societal optimum would be that everyone wears a helmet.

How could we get from the latter situation to the former? There are, actually, many ways a government could try to make that happen. One option would be to make helmets mandatory (and to enforce this rule at least to some extent) so that, presumably, people suffer a cost for not wearing a helmet, the fine they might receive when caught, which makes wearing a helmet relatively more attractive for them. This could be expensive, as you need to hire and pay police personnel to enforce the rules. Another option that the government could try to use is to fund an advertising campaign aimed at making people less worried about not being cool. They could try to make wearing helmets cool, instead, for instance. This could have just the same effect. Under both policy measures, if done well, the function would shift to the right, which probability theorists call a first-order stochastic dominance shift. This would have the effect of shifting the equilibrium proportion of helmet wearers up.

There is a third possible situation, that I depict in the figure entitled “interesting,” in which there are multiple equilibria. The low and high helmet-wearing equilibria are both dynamically stable (a dynamic process as the one I described above would lead to these points when the system starts in the vicinity of these points). The middle equilibrium is not dynamically stable. The lower equilibrium is initially more likely, as it makes sense to think that at some initial point, nobody wore helmets. If this is the situation that we are facing, then introducing a law to make helmets mandatory needs to be implemented and enforced only for a short time, until the proportion of helmet wearers exceeds the middle (unstable) equilibrium. After that we end up in the good equilibrium without any need for further enforcement.

This post has become a bit longer than I intended. Of course, one could debate whether or not there really is a social dilemma here (meaning my utility functions are possibly wrong). Perhaps, people just value the freedom of having the wind blow through their hair when scooting much more than the added chance of survival from a possible accident. Then a helmet law would make everybody just worse off. An advertising campaign might not be so bad in that case. There are many other things one could question, but I won’t do this now.